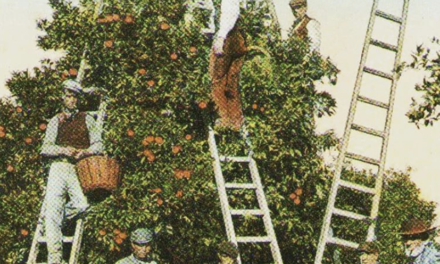

The history of Seville’s water goes back to ancient times. Much of this water, from places such as ‘Los Alcores’, 20 km from Seville, known since ancient times for its abundant water and famous citrus fruits, was channelled to the city through the so-called ‘Caños de Carmona’, a Roman aqueduct, later rebuilt by the Almohads, which supplied water to Seville until 1912.

It was in the 19th century when the City Council decided to incorporate the modern pressurised water system into the city. In those years, in the 1870s, water reached the city from the Santa Lucía spring in Alcalá de Guadaíra via the ‘Caños de Carmona’. In a city with approximately 12,000 houses, only 1,500 were supplied by this system. After the implementation of the new system, promoted by the English companies The Seville Warterworks and Easton and Anderson, half the houses in the city had pressurised water.

As an anecdote, the history of Seville’s water even has a football anecdote, as the Englishmen who came to Seville to modernise its water supply system founded the Sevilla Football Club in 1890.

Water from ‘Los Alcores’ for Seville

In 1871, the City Council opened a dossier for the supply of water by means of pressurised pipes. Until 1882, various proposals were received, for example from France and Belgium. On the 4th of March of that year the concession was granted for 99 years to an English engineer named George Higgin to supply the city by two systems: one for drinking water from Alcalá de Guadaíra and the other for irrigation by means of a direct connection to the Guadalquivir, the famous Sevillian river.

Higgin handed over the project to James Easton, one of the managers of the Easton and Anderson company, which specialised in supply works, who, in turn, reached an agreement with a company, which at that time had not yet been set up, to grant the exploitation: The Seville Waterworks Company (SWW). The works to provide the city with the network began in 1883, but they did not do so without problems, so that the actual transfer to the SWW did not take place until 1900. The Seville Waterworks, a company incorporated in London, was managed in Seville by Edward Johnston, who in 1890 was the first president of the Sevilla Football Club.

The works were inaugurated by Queen Isabel II, as can be seen from the silver shaft that was made and which is preserved in the board room of Emasesa, the public company that manages water in Seville, and were not without controversy. They were even suspended due to the press campaign against them. The workers even walked out, but it was so important for the city that its vital forces met at the initiative of Johnston at the headquarters of the Mc Andrew shipping company. The project was unblocked, and by 1884 the pressurised water supply was a reality in part of the city. The pipes began to be installed along the streets Génova and Gran Capitán, today Avenida de la Constitución.

The modern infrastructure was capable of carrying 100 litres of water per inhabitant per day from the Fuensanta and La Judía springs. The implementation of this system meant a spectacular change, especially for people with fewer resources. It should be borne in mind that in those years the city was very socially polarised, with great differences in the standard of living between the upper and lower classes. Specifically, a third of the population lived in the corrales de vecinos.

In those years, Seville had a triple water supply. The traditional one, from the Muslim period, from the ‘Caños de Carmona’, and the two that the English set up: the pressurised drinking water supply and the irrigation system via the Guadalquivir. In addition, the SWW provided pressure to those supplied by the water from the ‘Caños de Carmona’ to reach the upper floors. However, although the agreement between Seville City Council and the English company ended 99 years after it was signed, that is, in 1981, it was in 1957 when the City Council rescued the concession early, breaking the agreement with the English because, apparently, the water did not reach a large part of the city with sufficient pressure, something that contravened the agreement.